Clare Town: Industrial Pioneer or Tourist Town?

Please note that this article is by no means a definitive piece. Though we have gone to great lengths to try and make this article as factually correct as possible, we accept that some of the information here is based purely on human memory and may differ from the information others may have. We aim to continue adding to and editing this article as regularly as possible and ask that if the reader does find any of the information below either missing a relevant part or misinformed in any way, that they either leave a comment at the bottom of the listing or, alternatively, email any additional pictures or relevant knowledge to info@suffolklatchcompany.co.uk.

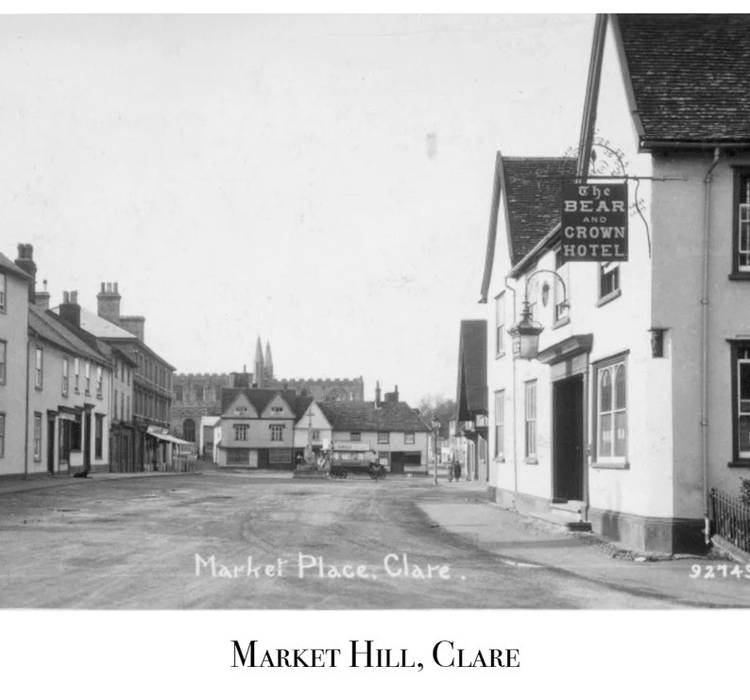

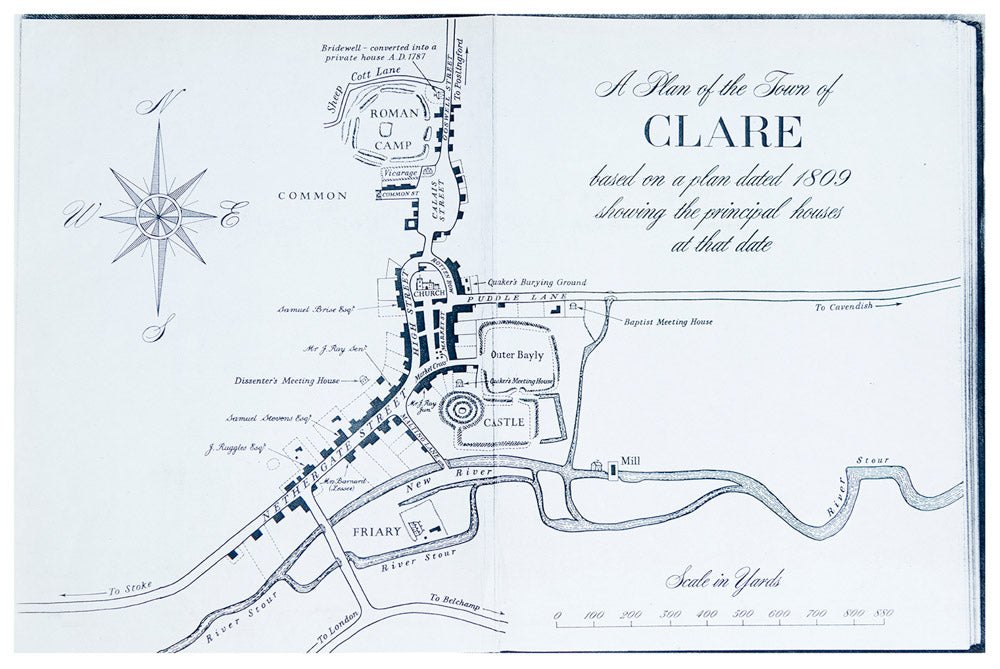

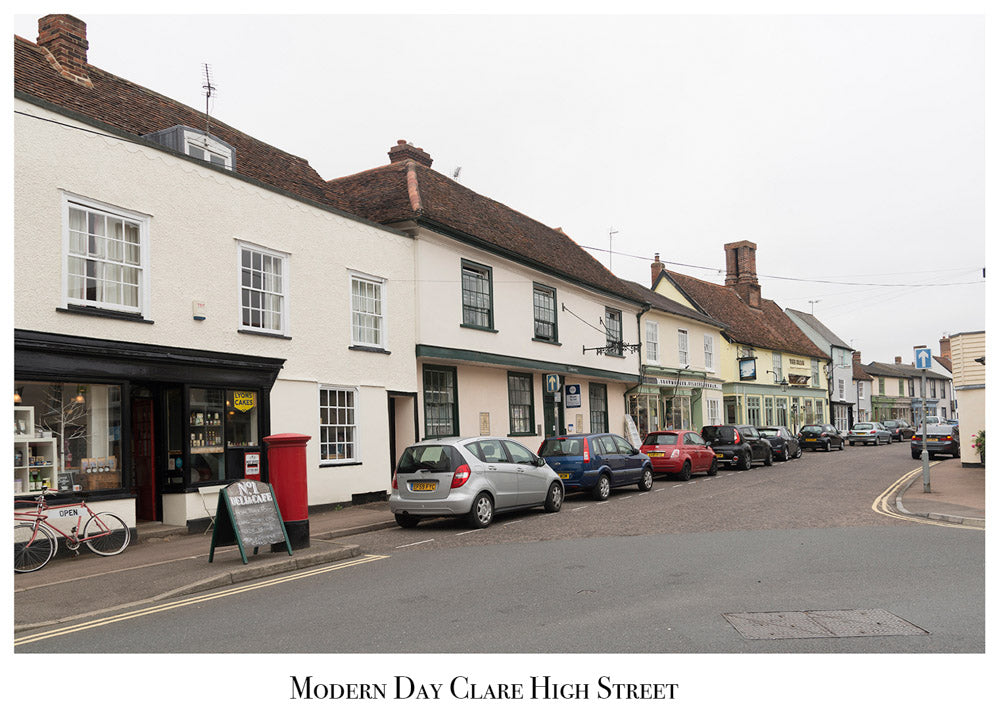

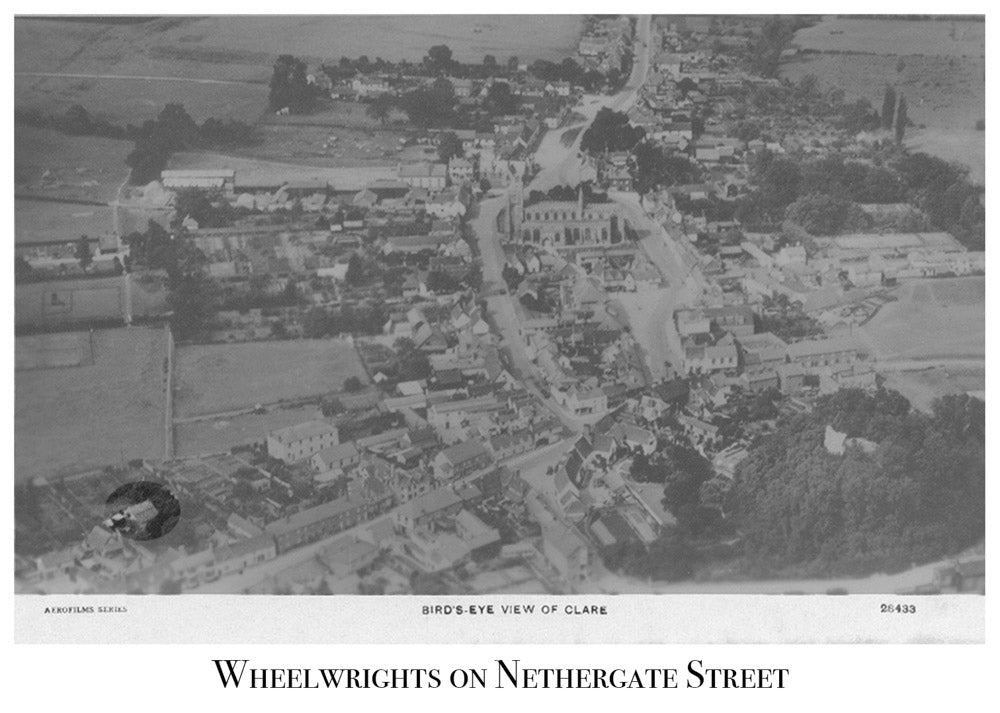

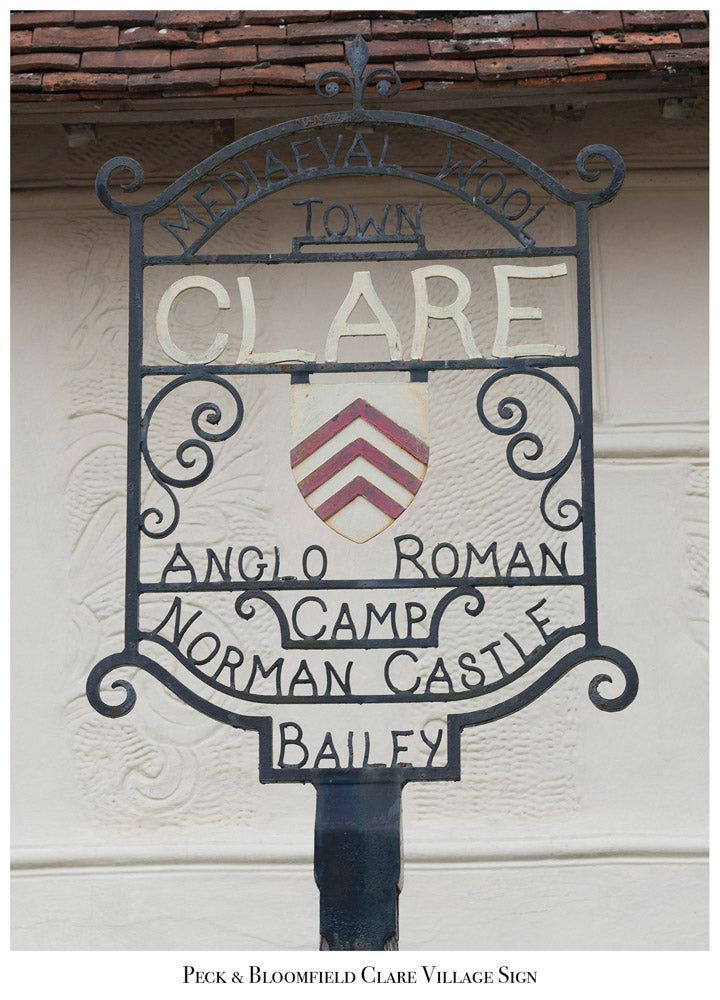

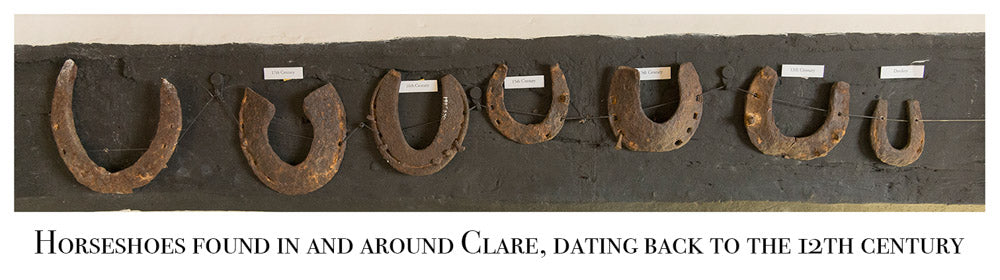

Situated along the River Stour in Suffolk, the small town of Clare sits testament to the rich history woven throughout East Anglia. This history lays across a sprawling spectrum of industries, with everything from cloth making to agriculture featured in tourist guides across the globe. It is, however, one particular area that we are fascinated by here at The Suffolk Latch Company- the manufacture and trade of ironmongery within the town from the early 1800s to present day. With the inclusion of wheelwrights, farriers and brick makers, this article is a compendium. A journey through time, looking at how Clare has changed from a self-sufficient centre of industry to the picturesque tourist town that we are familiar with today.

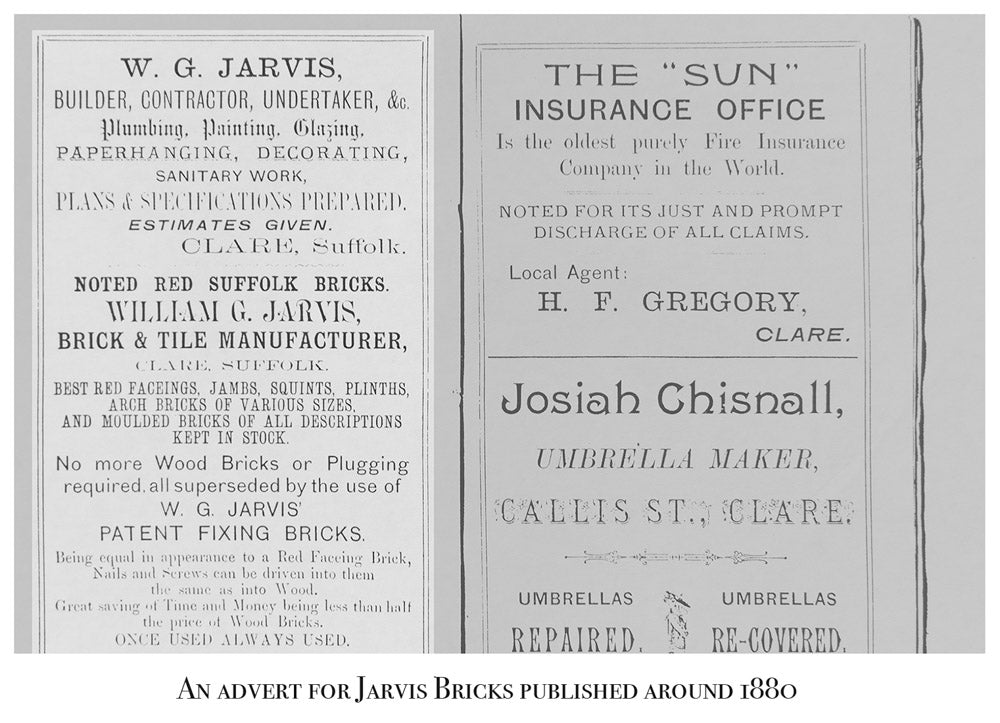

One of the first forges on record was established in the 1830’s by John Jarvis, a founder of the brick makers known as Jarvis (William George & Son). Built to manufacture his Clare Jarvis bricks, the forge was in operation until 1914. Located along Cavendish Road, where the Forge House is now situated, it was shut down during the First World War due to the worry that the kilns would attract the attention of enemy soldiers and raiders. Though this was intended to be a temporary closure, the brick works never opened up again after the war.

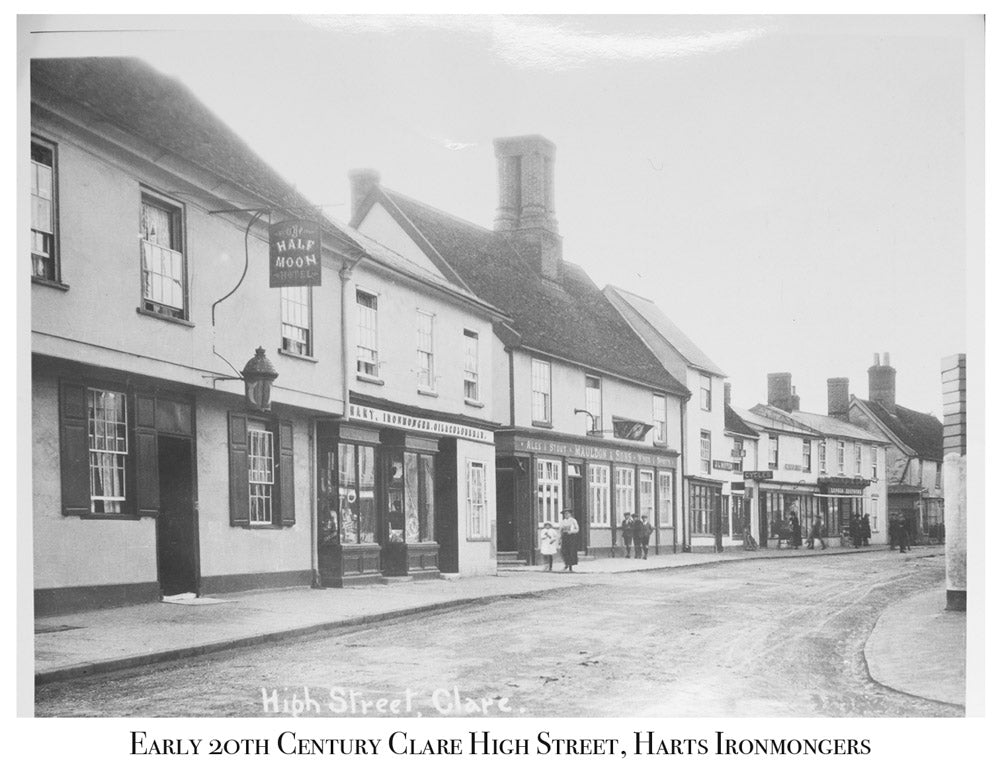

Around the same time that John Jarvis created his forge, Clare’s first ironmonger John Sadler opened his store in the High Street, before being succeeded by Thomas and Charles Wade in the 1840’s. The ironmongers sold a variety of goods, with most of the merchandise manufactured on site. This was then taken over by J. E. Hart, who was succeeded by his son E. F. Hart who died in 1934. Ernest Willis took over shortly after before retiring in 1980 and was followed by J. Thomas and A. F. Hurrell. The business still runs to this day under the name of Hudgies Hardware. Though products are no longer made on the site of the ironmongers, they still stock a veritable selection of items, with everything from nails to tableware on offer.

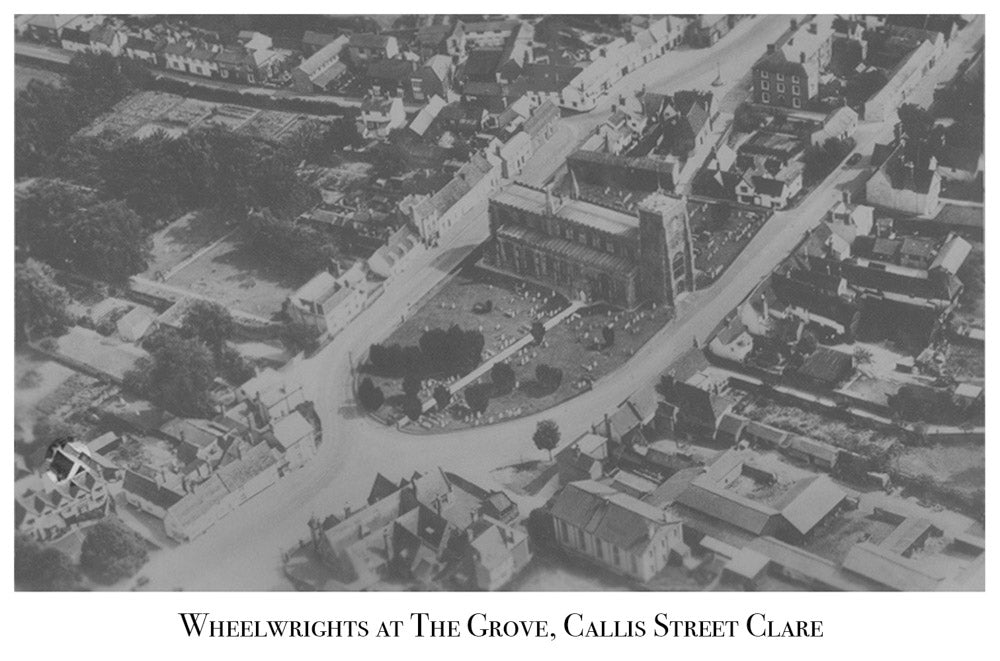

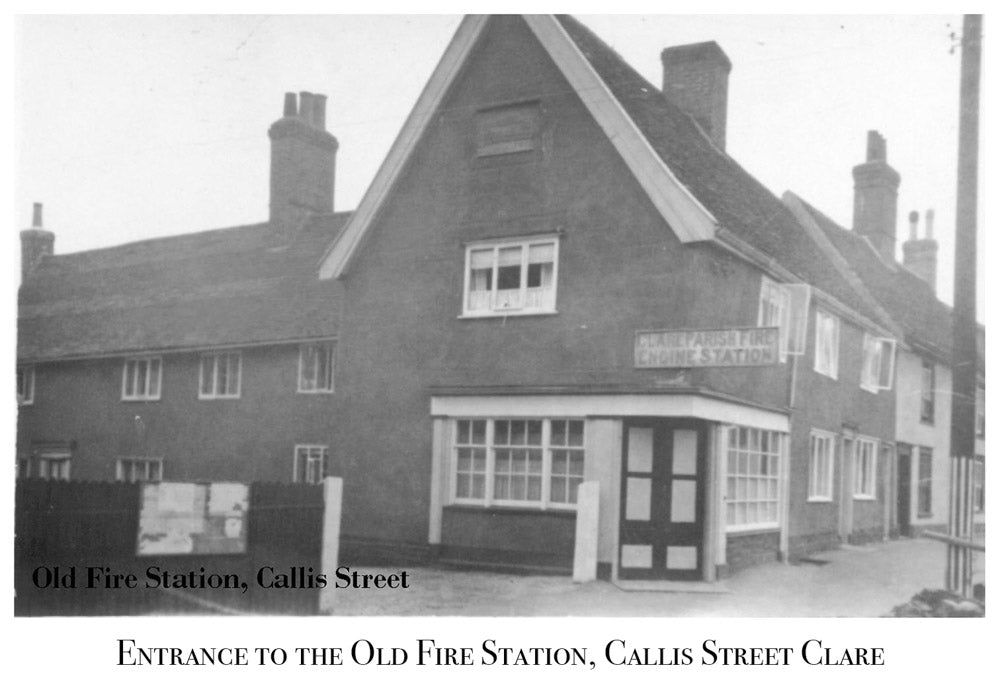

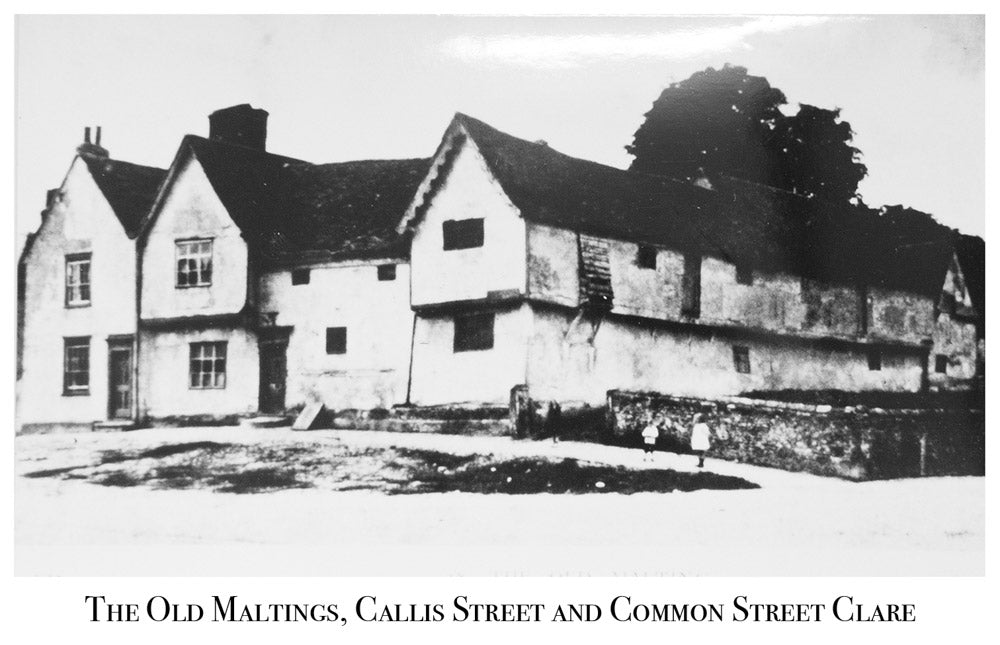

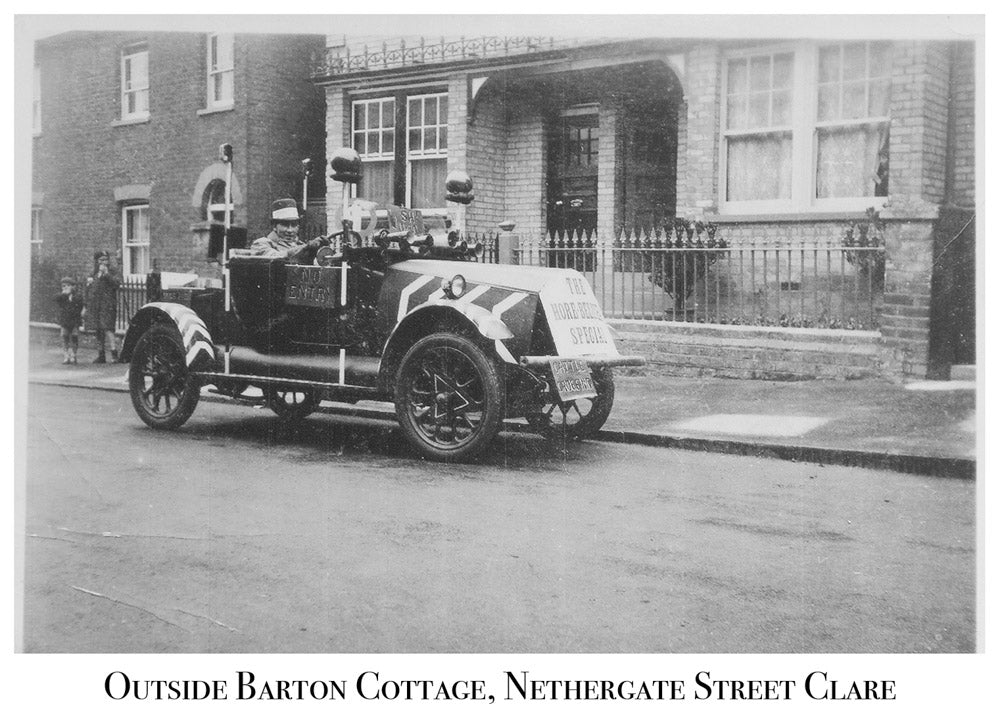

Another popular occupation in Clare was that of the coachbuilder, with Deeks and Hayward establishing their business in the 1850’s. Located to the South East side of the town where Tudor Cottage stands, their work involved car repairs on a relatively large scale and supplying the Bell Hotel in Clare with wagonettes that could be hired out to anyone wishing to ride around the area. On top of this, they painted carriages and once their business had become more prominent within the area, they crafted them for Newmarket races. In 1885, another coachbuilder by the name of Eli Wiffen took up the trade at Grove House on Callis Street. His work was done predominantly from the workshop situated behind the five gabled house and was home to a fire engine toward the end of the 19th century.

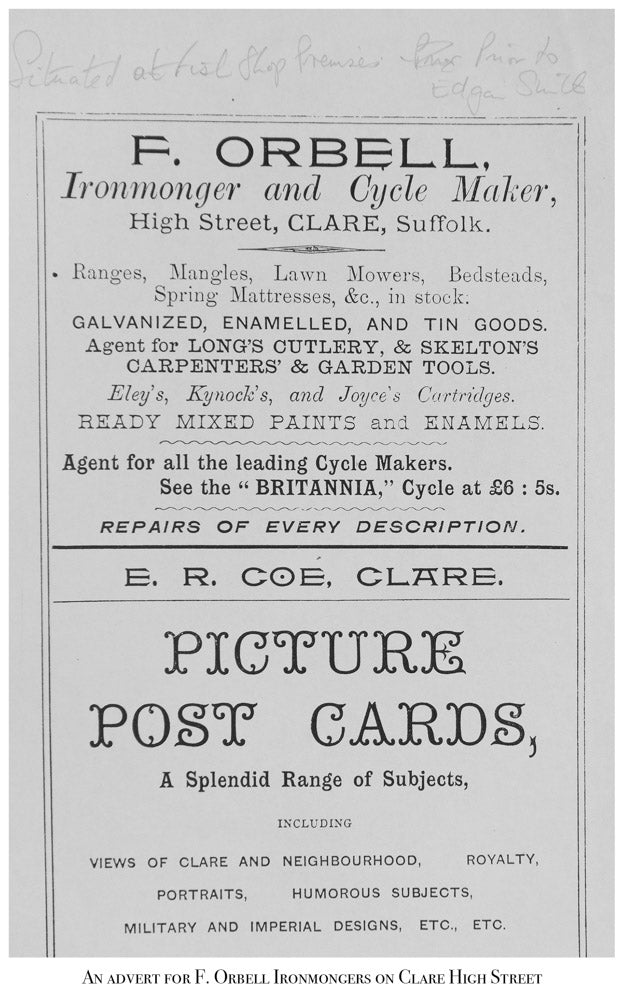

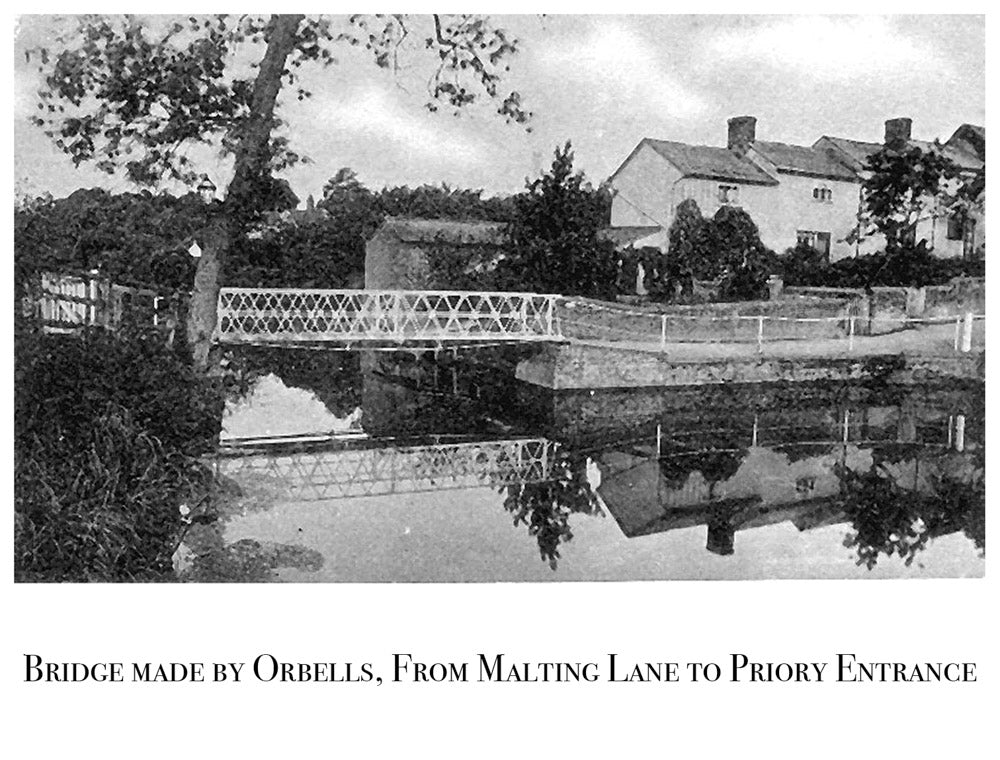

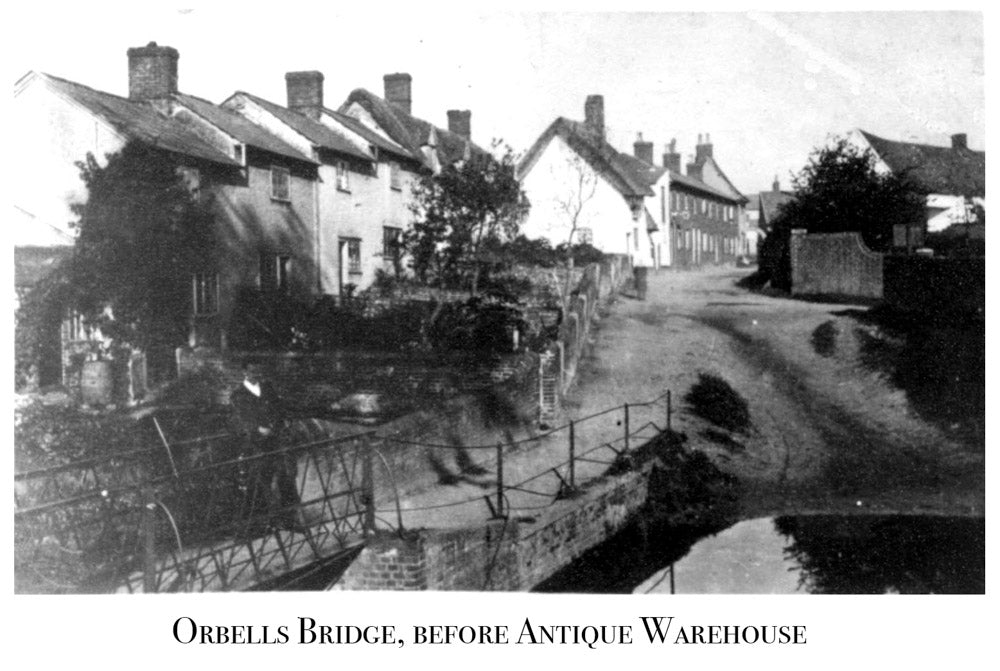

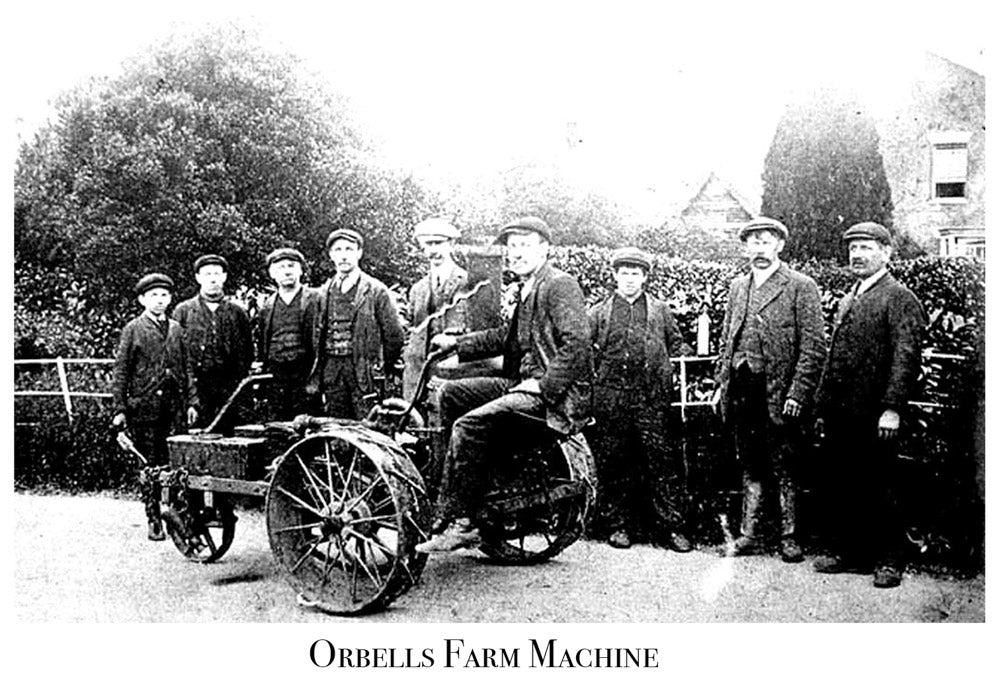

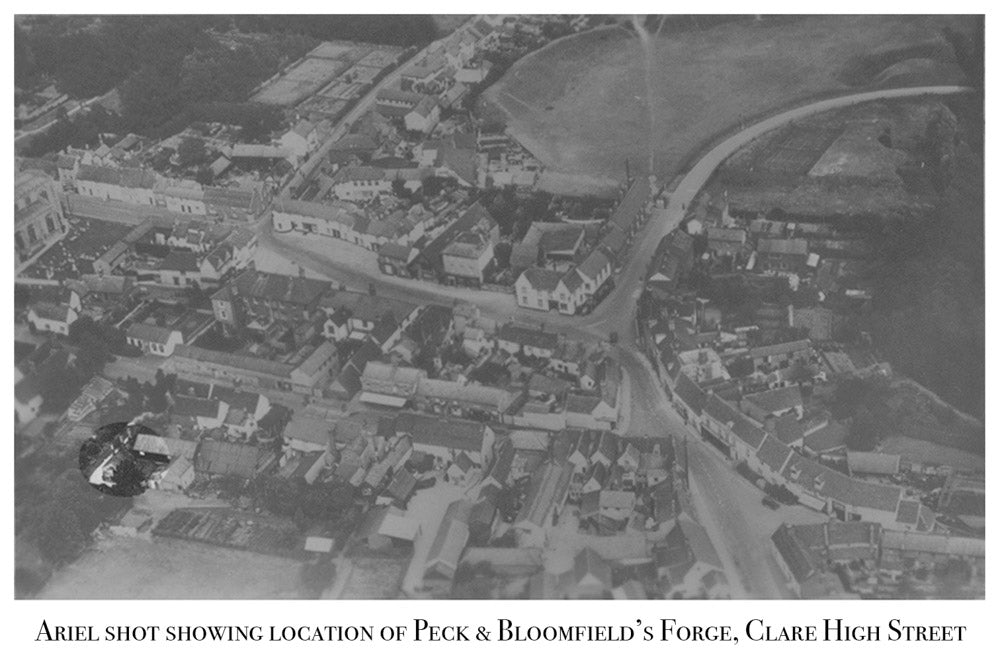

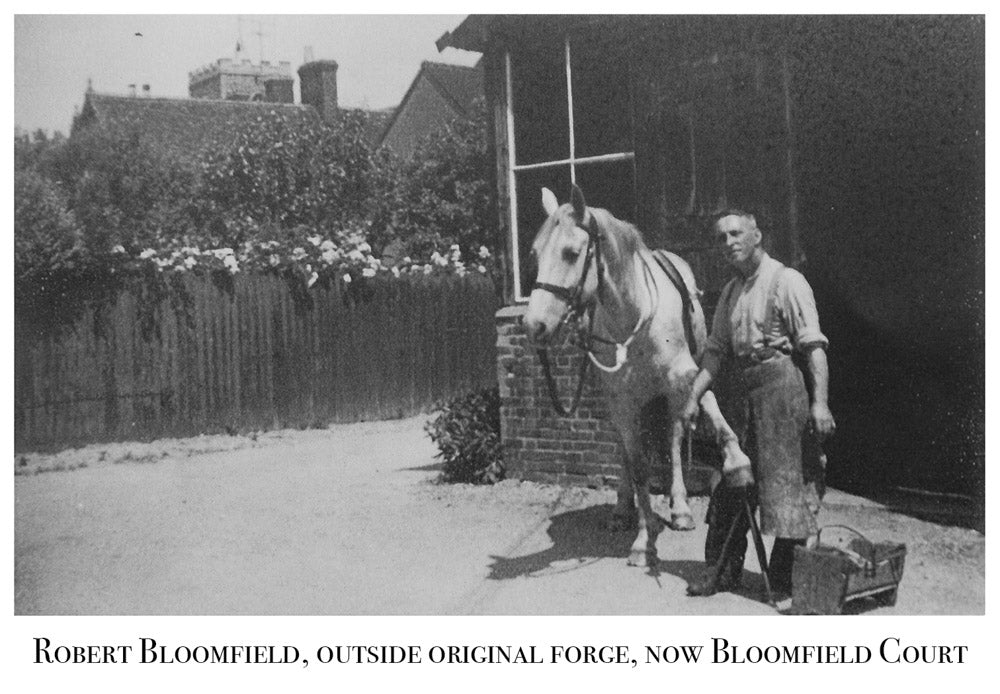

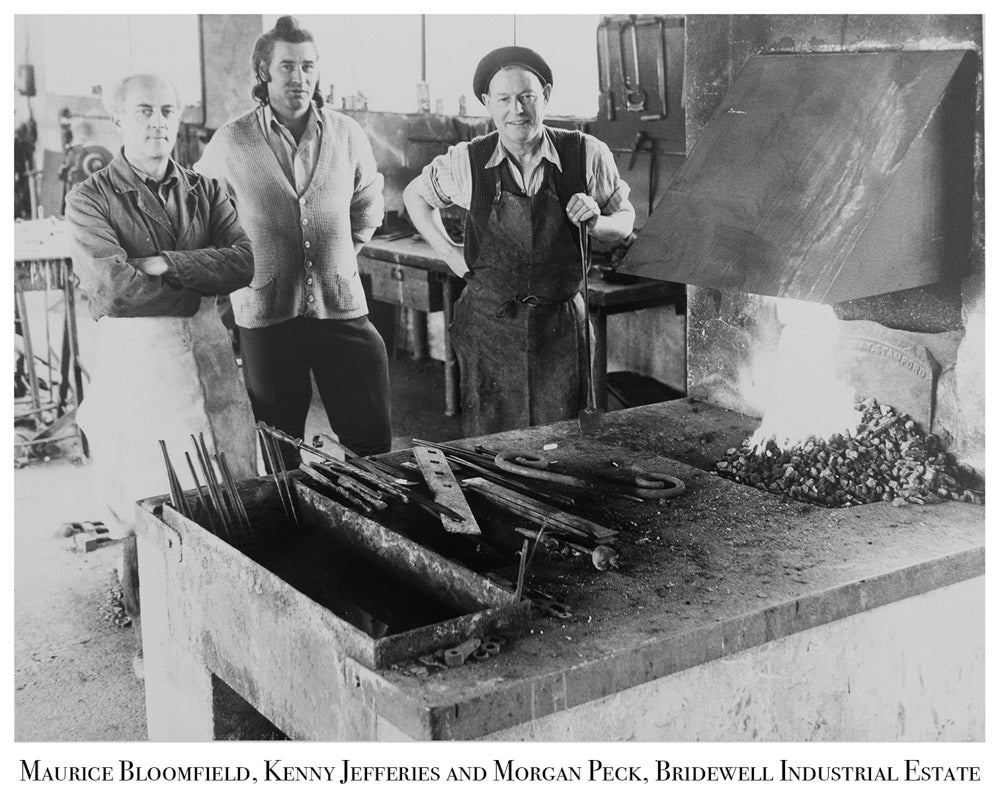

Coachbuilders and wheelwrights often worked in tandem with the local blacksmiths, with the latter forging iron tyres to fit their wooden wheels. This brings us to one of the more prominent industries within Clare- blacksmithing. From the enigmatic Old Smithy cottage in Chilton Street to the illustrious corporation of Peck and Bloomfield, the remnants of smiths can be found throughout the town. However, Orbells Yard that once sat along Cavendish Road is a far cry now from what it looked like back in the 1800s. Thomas Orbell then moved to Clare High Street to the back of where the Jug and Bottle is situated today. Amongst other things, Orbell ironmongers made the bridge along Malting’s Lane and a farming machine seen in one of the adjoining photographs, its use unknown. In the 1920s, Orbell was looking to hire someone to shoe horses, which introduced Robert Bloomfield into the area after his stint in the First World War. After Tom Orbell retired, Bloomfield took over the business with his son, Maurice Bloomfield, and his nephew Morgan Peck until his retirement in 1969.

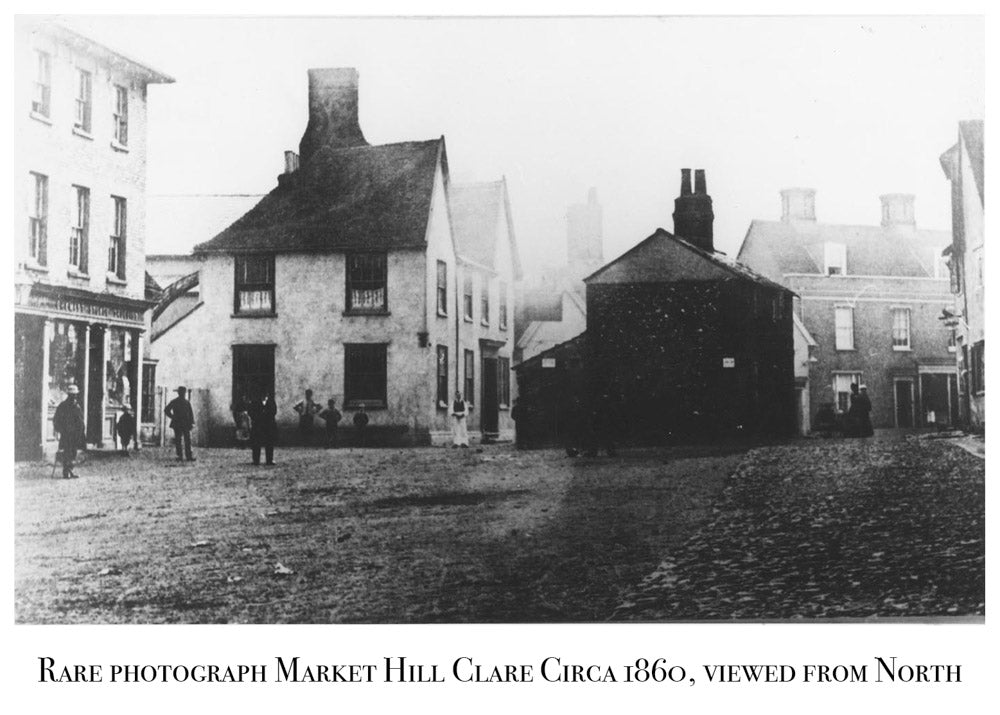

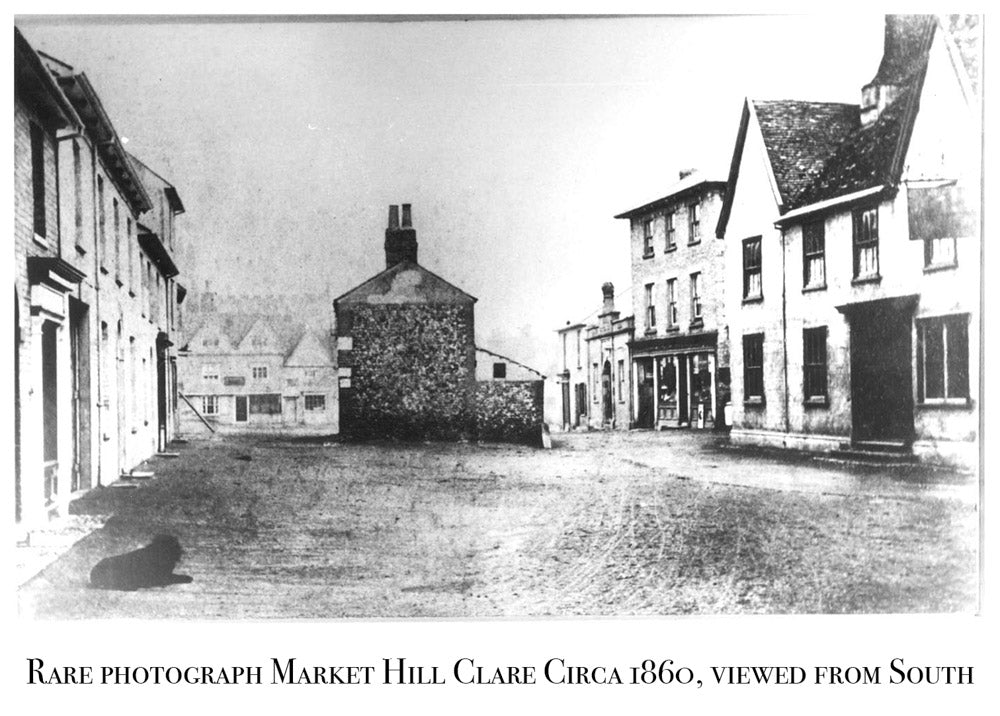

The men in the above picture are stood roughly by the red brick house seen in the picture below.

Behind the lady would have been the original Clare Fish and Chip shop in the building made of corrugated iron.

Orbells Bridge before the Antique Warehouse was built behind it. As you can see in the image, thatched cottages stood previous to its construction.

Following a meeting with Gloria Orbell and Robin Stone, I am pleased to inform you that they have both been working hard for a number of years on producing a book relating to the modern history of Clare. Of particular interest will be details of the farm machine pictured above, at this stage I will say no more but hopefully I will be able to provide further details as the book gets closer to print.

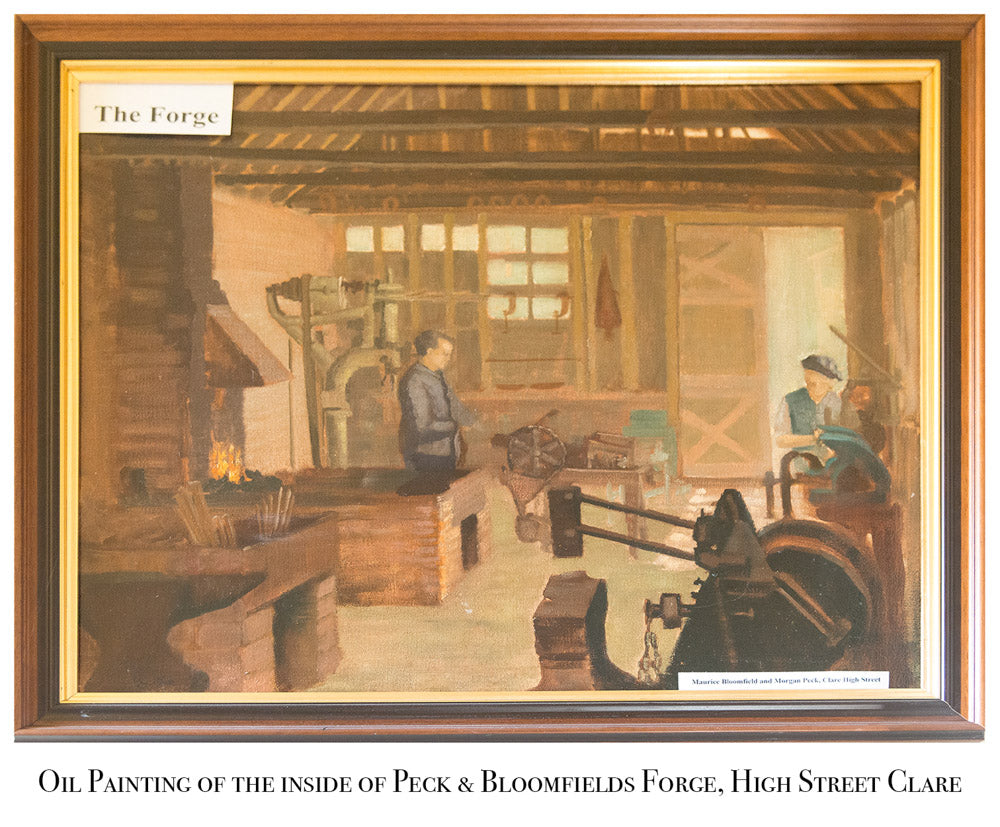

During Bloomfield’s stint in the High Street, his work was put on display to the general public using the window facing out onto the street. The people of Clare would have seen all sorts of ironmongery featured, with everything from window brackets to fire baskets on show. All of their products were made in a workshop to the right hand side, where Bloomfield Court stands today, with Robert Bloomfield’s office to the back of what is now the Jug and Bottle. Between the beginning and the end of his time in Clare High Street, Robert Bloomfield would have carried out a wide variety of jobs, mostly in relation to local farms and their machinery. Robert, Maurice and Morgan would have repaired hundreds of harrows and thousands of trailers, whilst also assisting the local wheelwrights in the production of wheels. The wheelwright’s wooden wheel would be given to the blacksmith following its completion, so that they could make the iron hoop tyre to fit the outer edge. Whilst red hot, the tyre would be fit to the wooden wheel using hammer and nail before being doused with water to fix it in place.

This Oil Painting can be found in Clare Museum.

Gradually, as rubber tyres replaced iron ones and horses were replaced with tractors, Bloomfield’s business evolved and changed with the times. Whilst he still carried out farrier work, he did far less than when he worked for Tom Orbell in the 1920’s. The agricultural side of their business took precedent over anything else, and when they eventually moved to Bridewell Street, they manufactured their own harrows and trailers rather than just repairing ones brought to them.

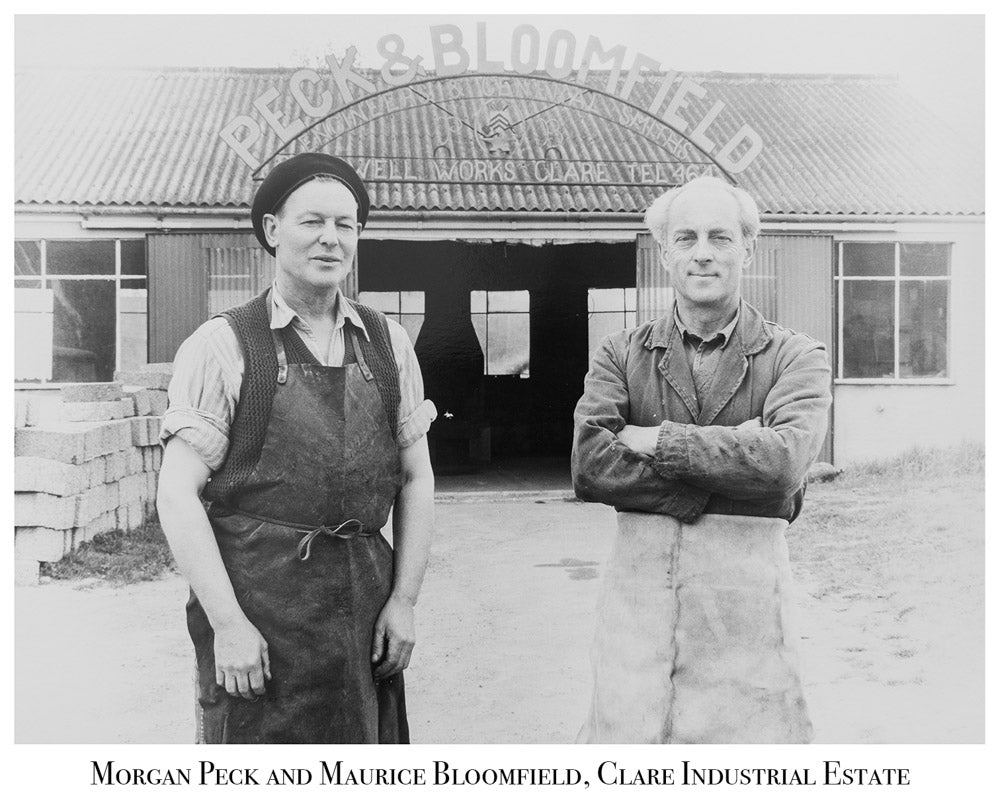

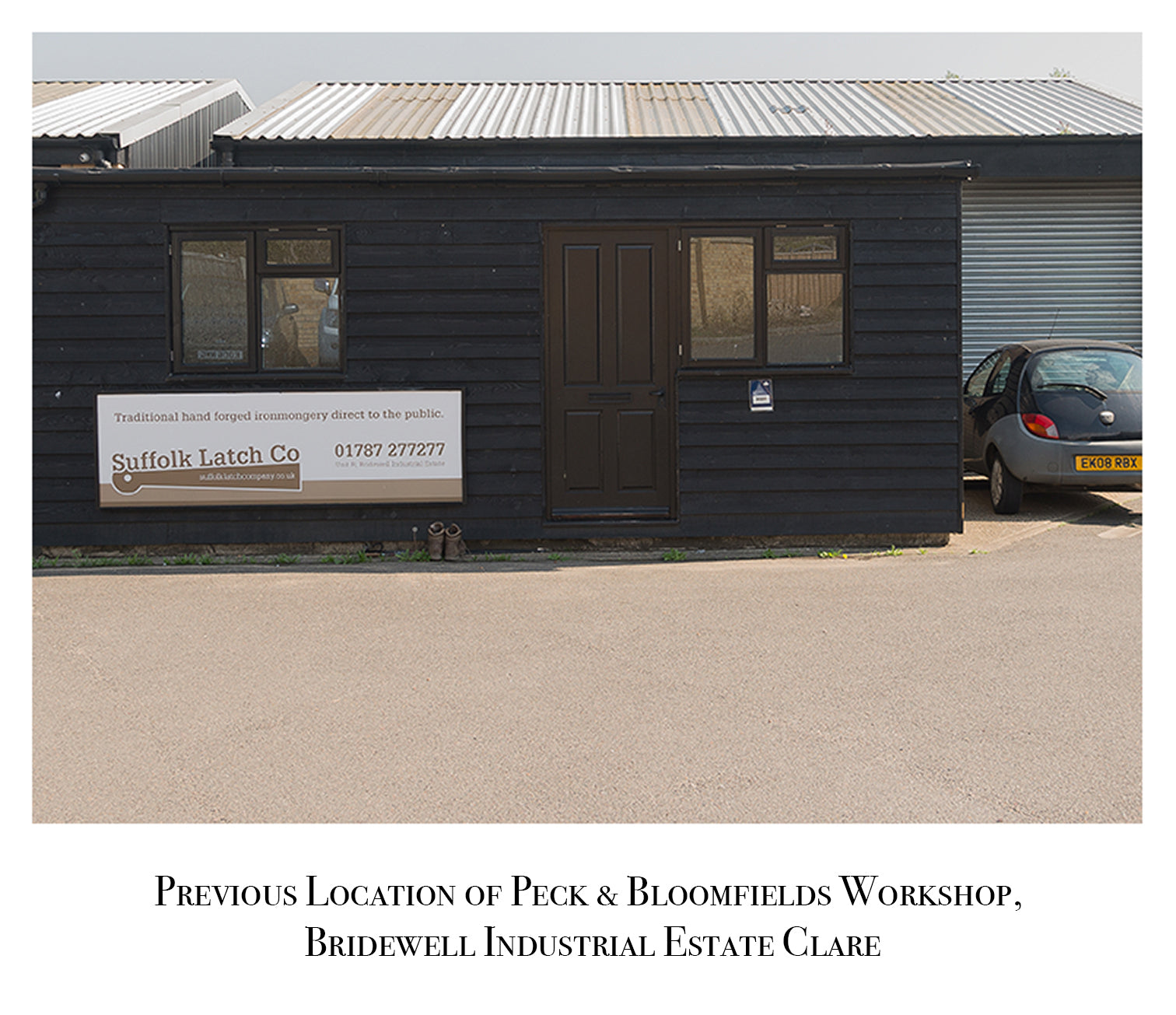

The move occurred in 1965 just prior to Robert Bloomfield’s retirement. Bloomfield had the industrial estate on Bridewell Street built, his workshop being the main unit on the plot. Following his retirement a couple of years later in 1969, Maurice Bloomfield and Morgan Peck took over the business and christened it the ever notable ‘Peck and Bloomfield’. This is when the construction of their own farm machinery truly began, the massive increase in space allowing for bigger projects that couldn’t have been achieved previously. They would piece together their own harrows before painting them in vibrant reds or blues, leaving them to dry on the meadow to the side of their workshop. This meadow would soon become what is now Bermuda and Bridewell house, where both Bloomfield and Peck both lived until later in life. However, as with the death of their fathers work with horses, the farm work also met a gradual decline in business due to the introduction of chemical sprays. Thus Peck and Bloomfield had to change their focus once more, this time to the wrought iron side of blacksmithing.

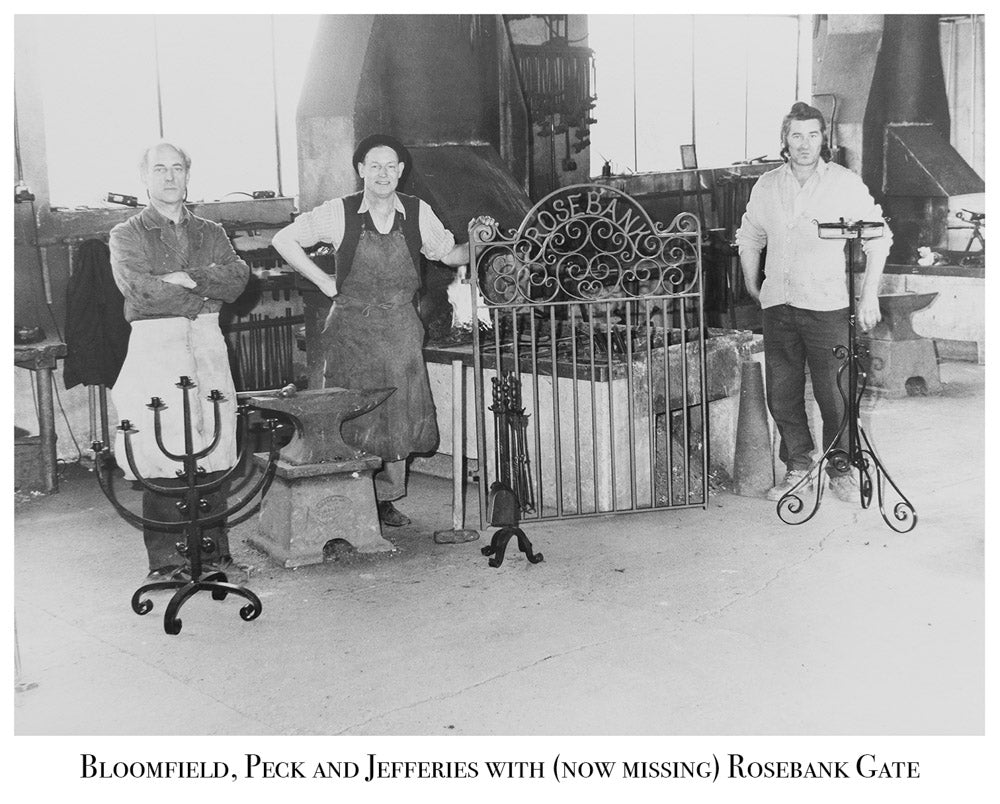

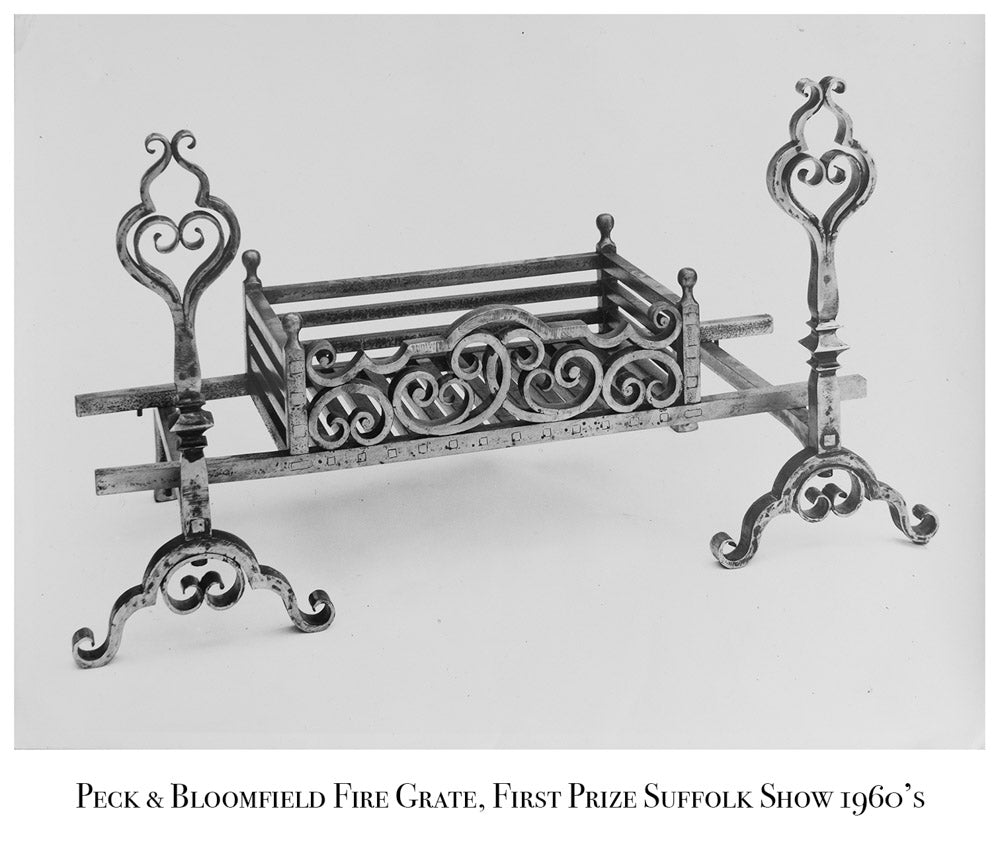

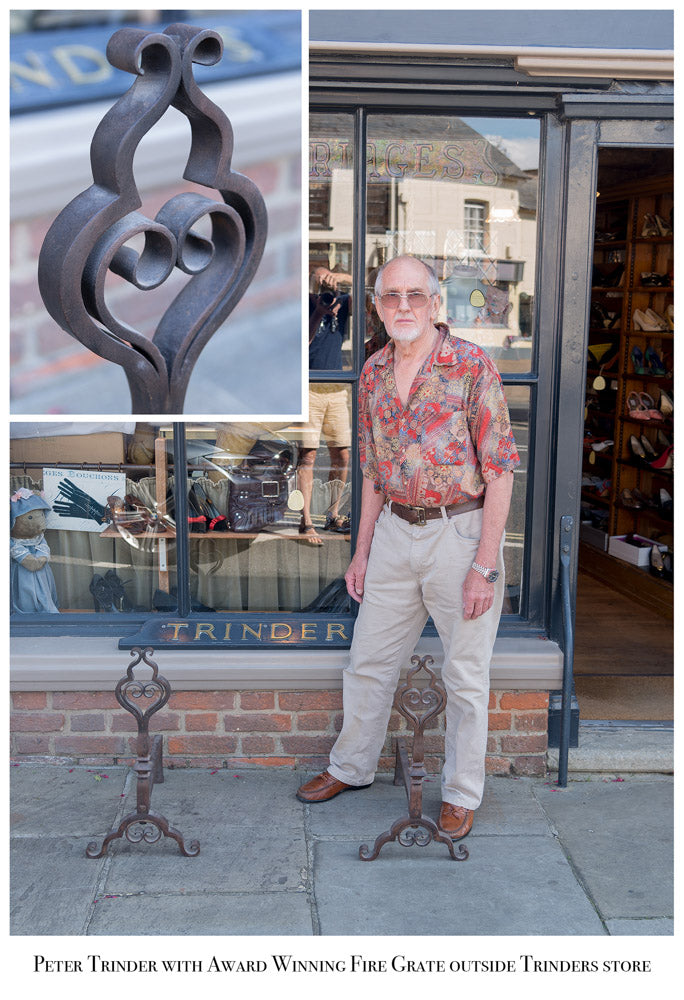

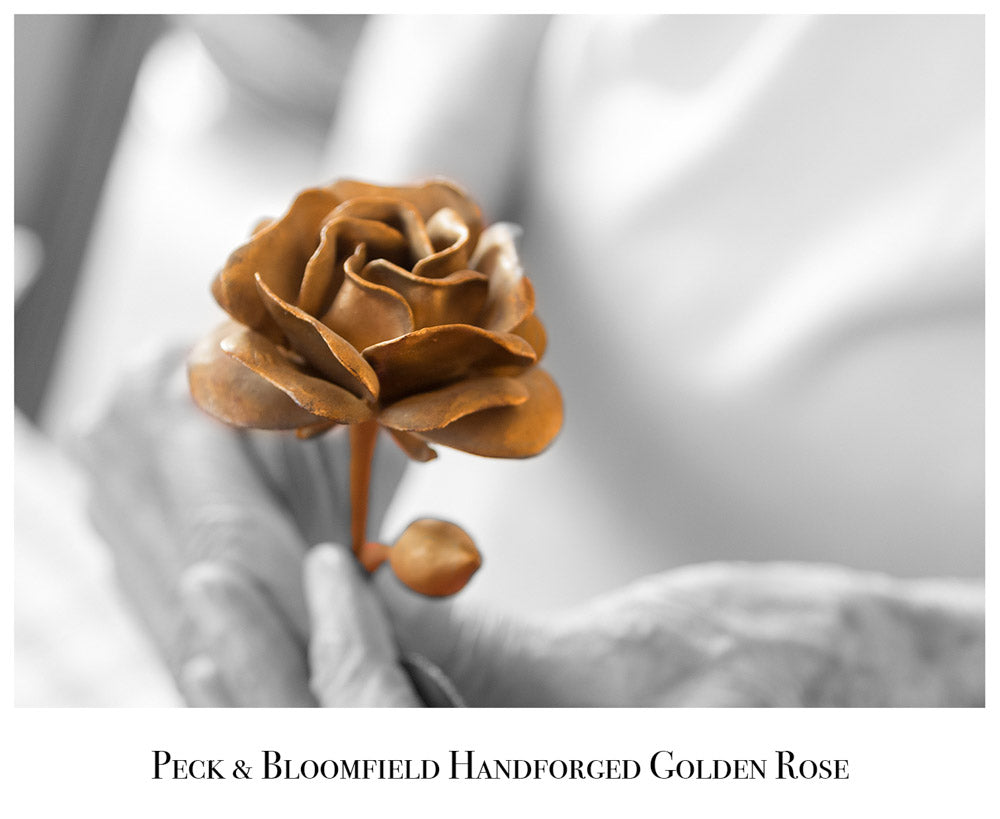

This began when the Rural Industries Bureau invited Morgan Peck and Maurice Bloomfield to learn how to work with wrought iron as part of a scheme to make local crafts popular again following the war. Their works quality increased in leaps and bounds, with some of their later pieces winning numerous trophies at different competitions within East Anglia, including the well renowned Suffolk Show. Their pieces garnered interest from royalty and trades people alike, with craftsmen trading their pieces amongst each other during the events.

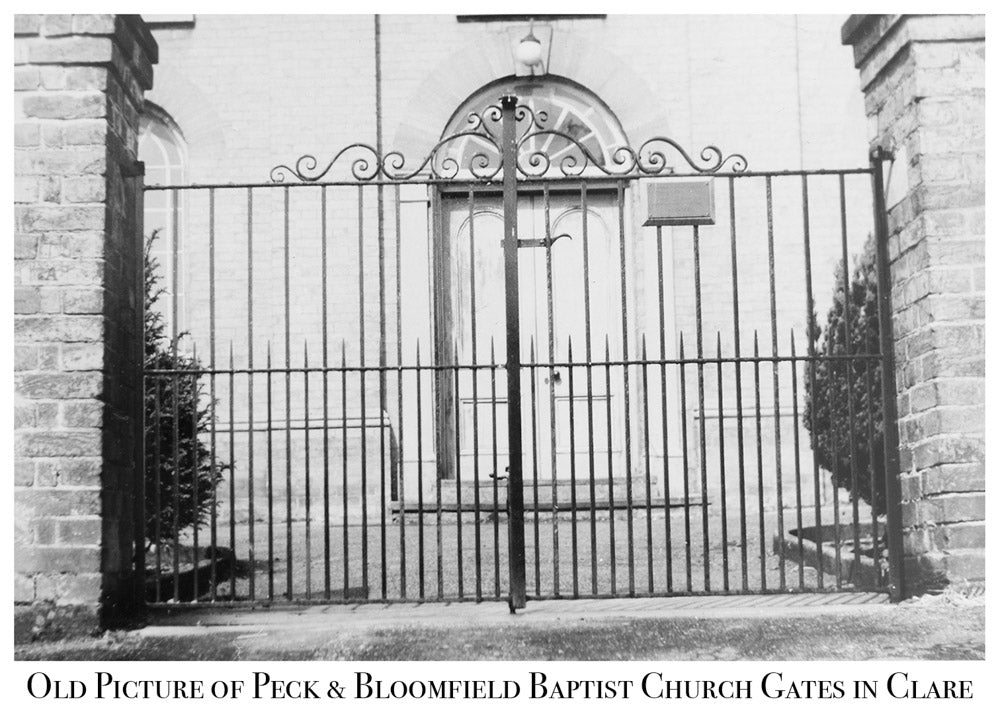

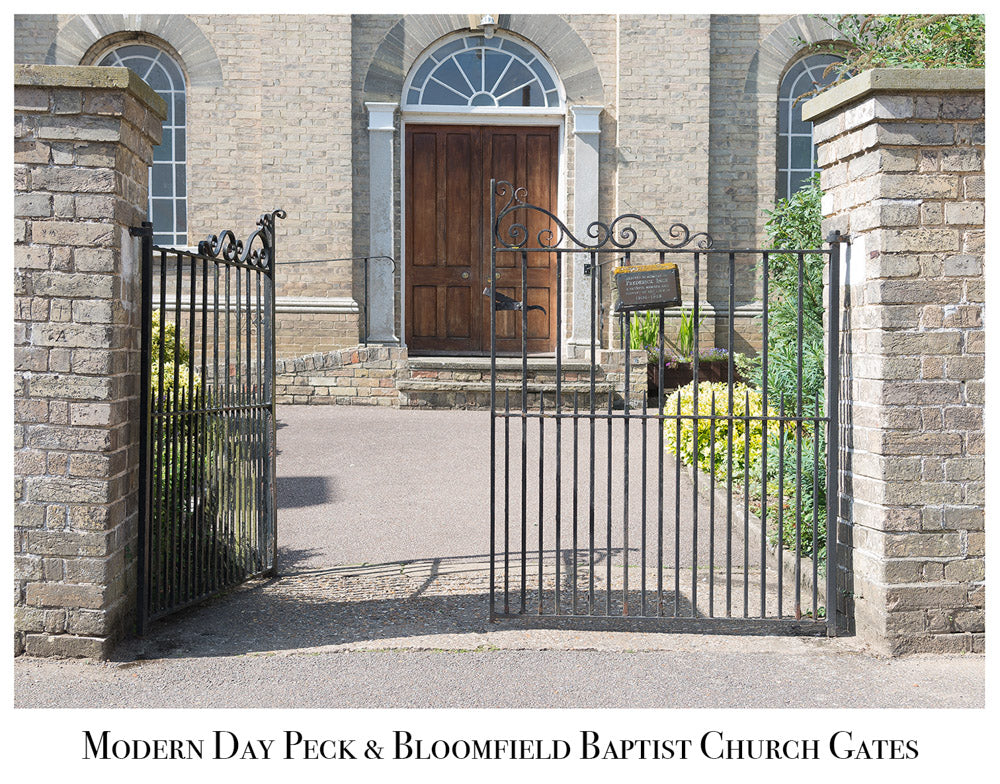

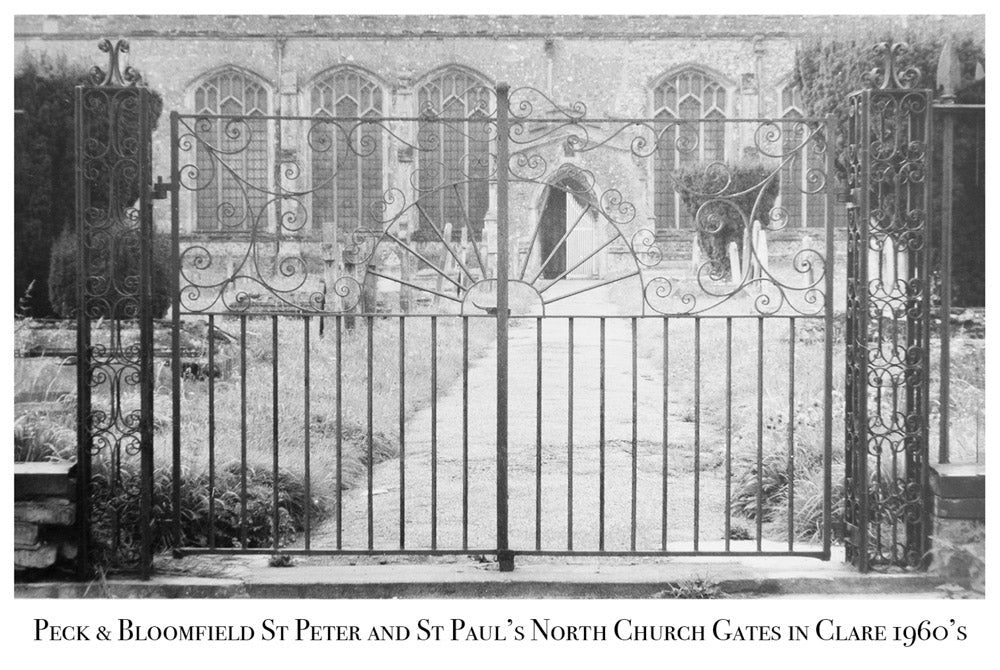

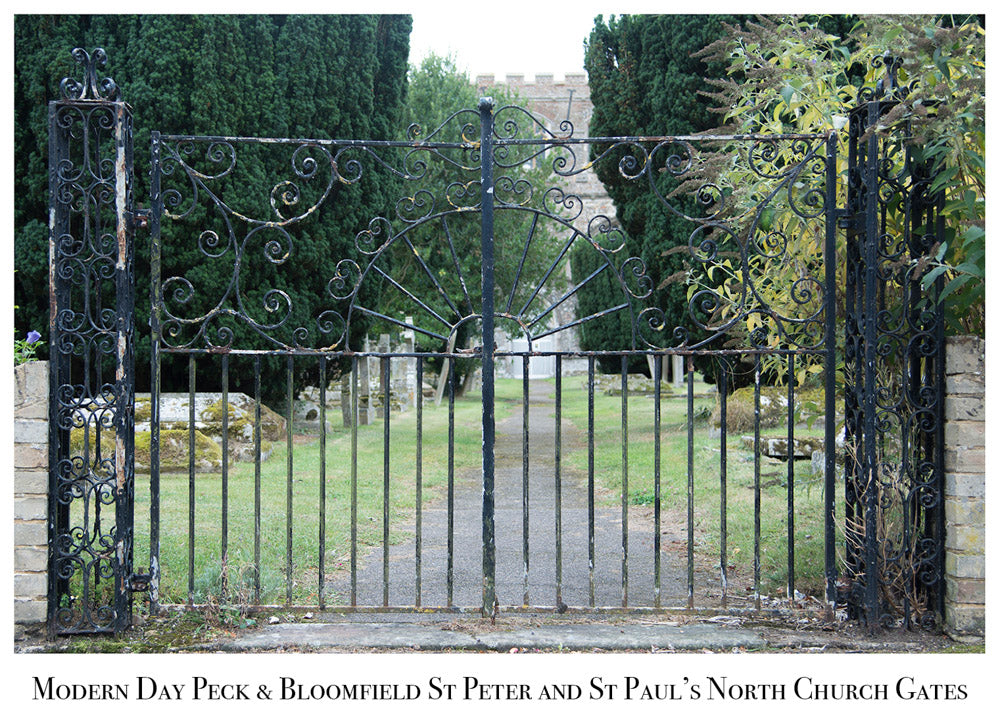

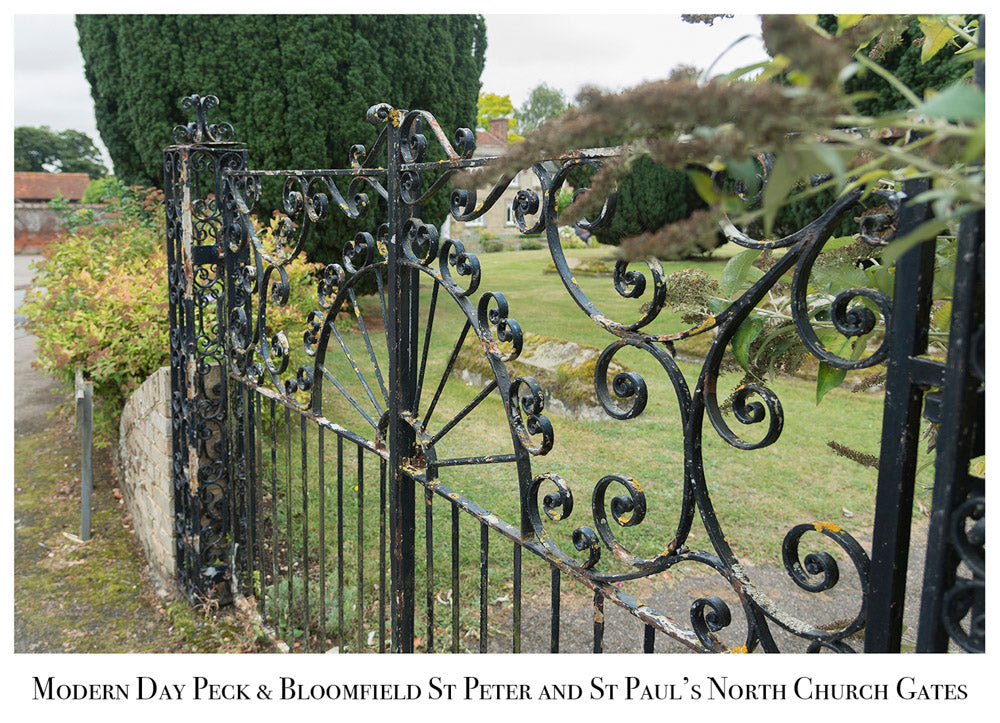

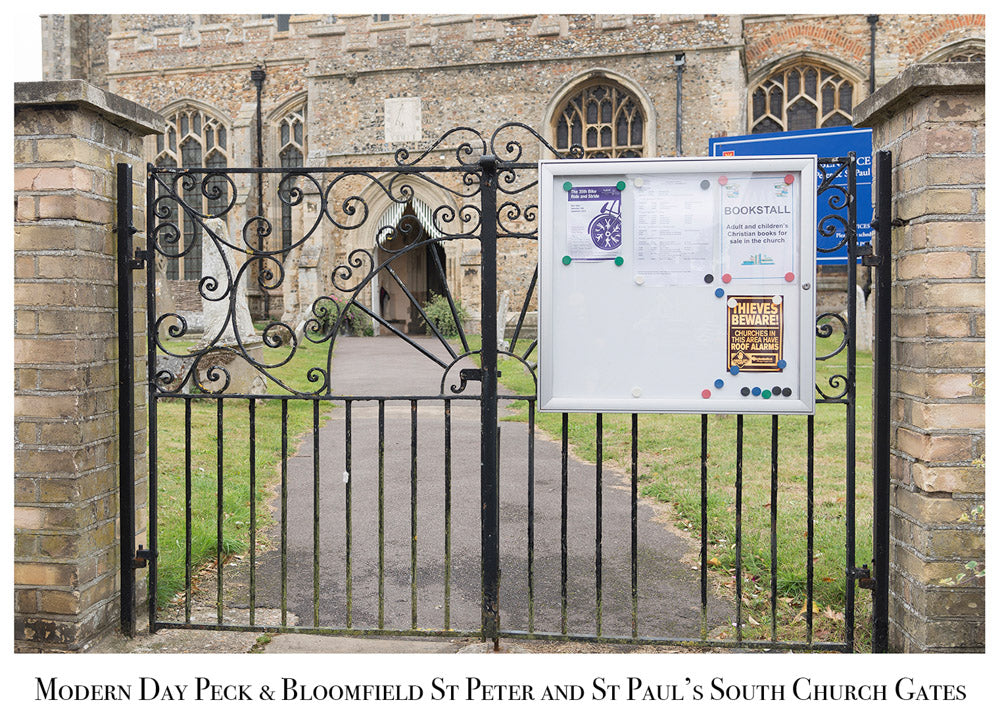

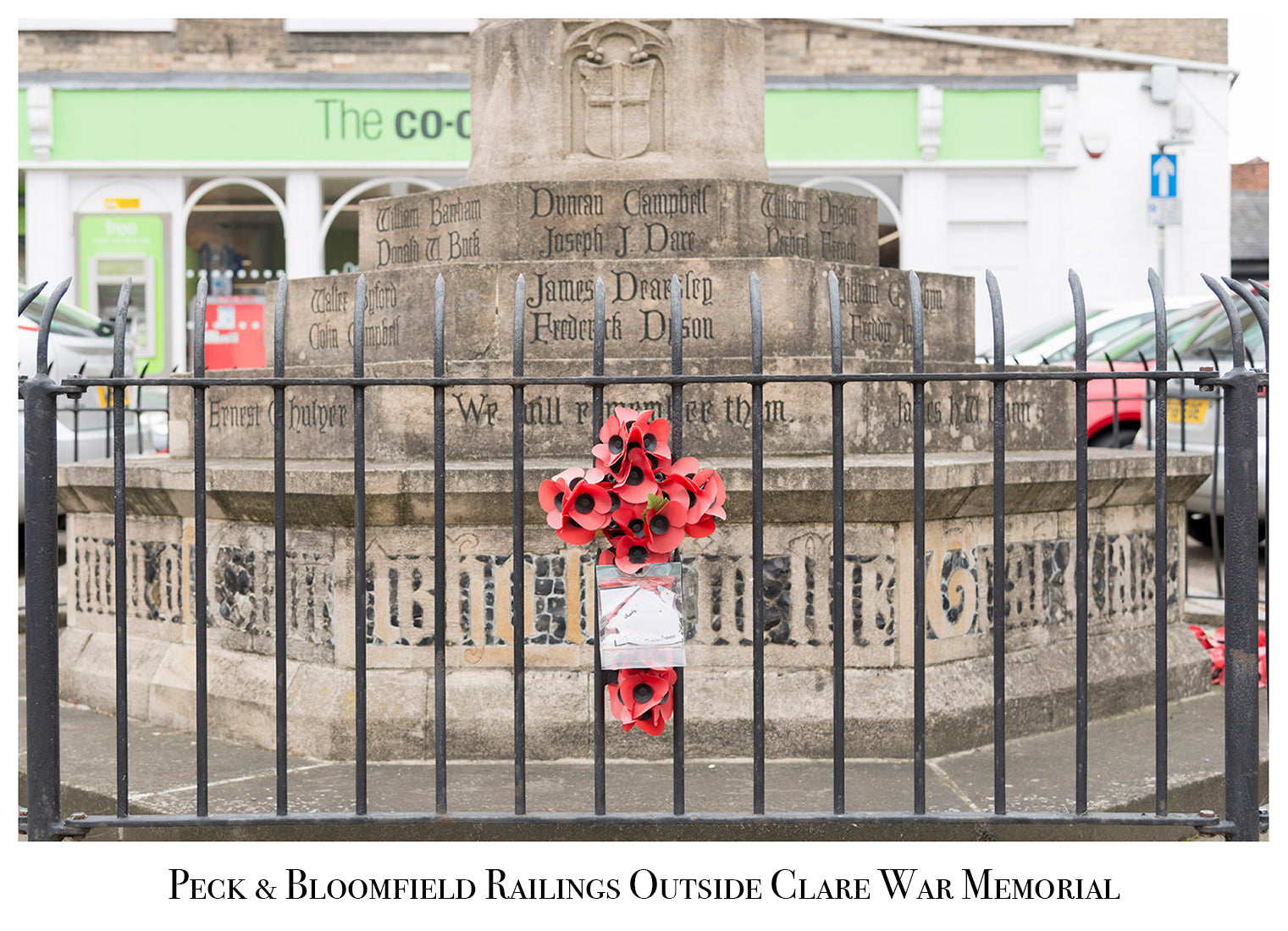

Once at this level within their craft, they started making signs for villages across East Anglia, with Hellions Bumpstead and Hundon just two of the locations with work featured. However, their work went still further afield, with one weather vane making its way over to Japan, their ironmongery proving a big hit with visiting tourists. Peck and Bloomfield’s work is not as prominent in the surrounding areas as it once was, but there are still surviving pieces dotted around the neighbouring areas to this day. To name but a few, the church gates in Clare were made by them, as was the lamp in Hundon church. Peck and Bloomfield would not only have crafted these themselves, but also fitted them too, using their Bedford and Morris van to transport their ironmongery to the specified area.

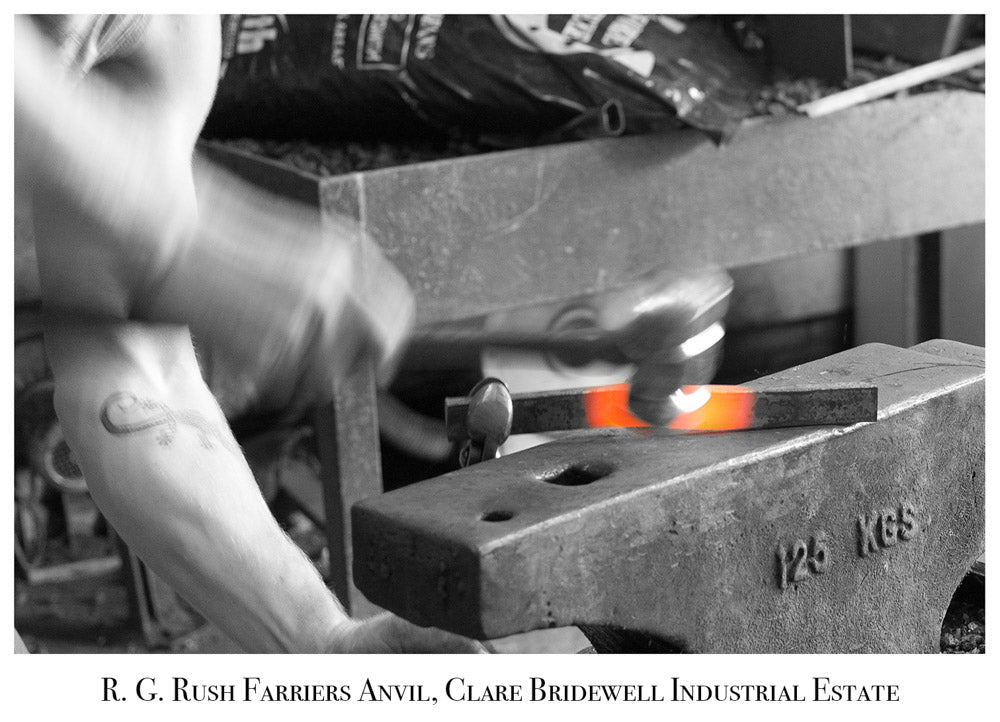

Though Clare is very different from the industrious town it once was, there is still metalworking being carried out to this very day. R. G. Rush Farriers was established in 1965 in Chelmsford by Robert George Rush and moved to Clare in 1977 to Rats Castle, a secluded area to the east of Clare town. Now their forge is situated at Bridewell works, the same industrial estate that Peck and Bloomfield founded in the 1960’s. As Robert Bloomfield and his predecessors once did, R. G. Rush Farriers run their business in the traditional sense, with 20% of their horseshoes hand made in their forge and the remainder purchased from outside sources. Everyday there are new apprentices practicing shoe making in the forge, the ring of hammer on metal a welcome song for the other firms across the industrial estate. Though the trade of local blacksmiths and wheelwrights may have declined over the past century, businesses like R. G. Rush Farriers stand testament to the once prominent industrial age that spanned the majority of the UK and Clare itself.

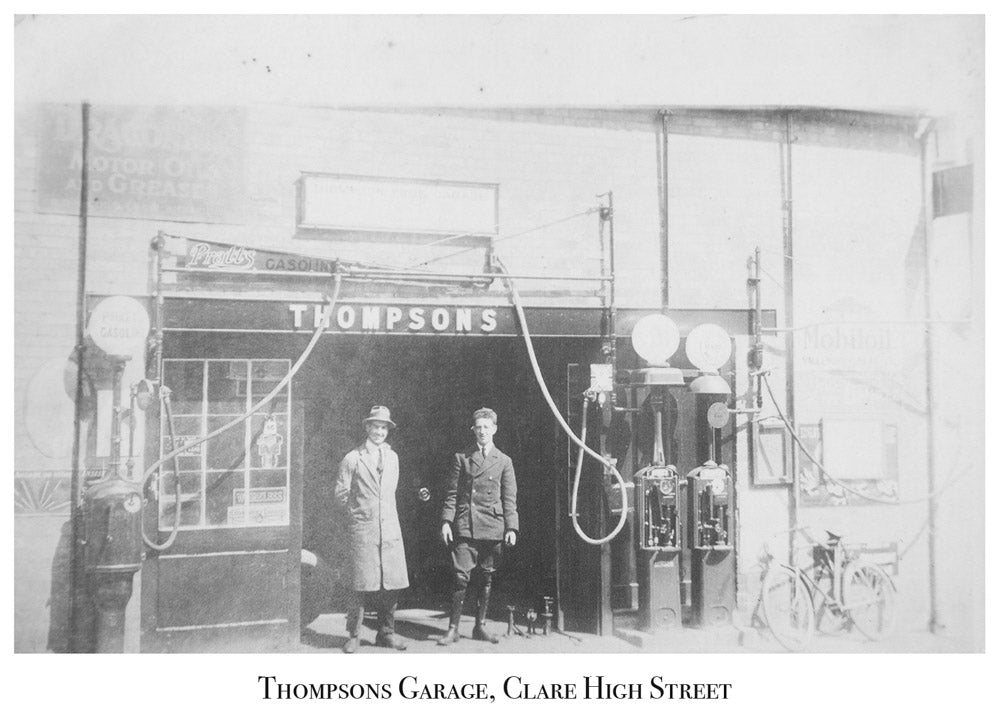

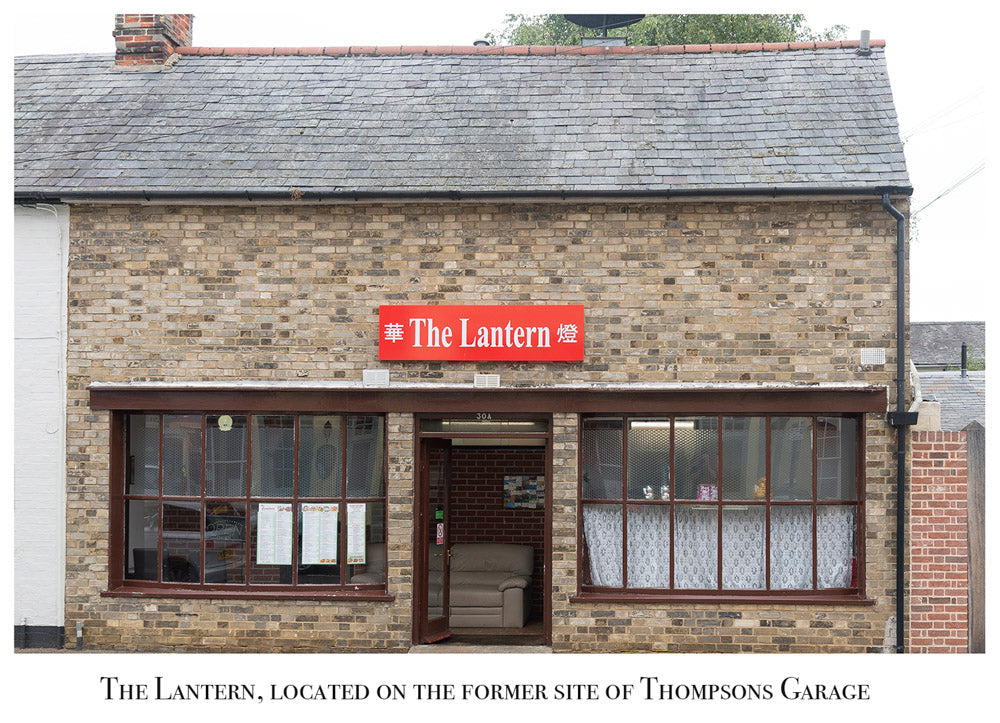

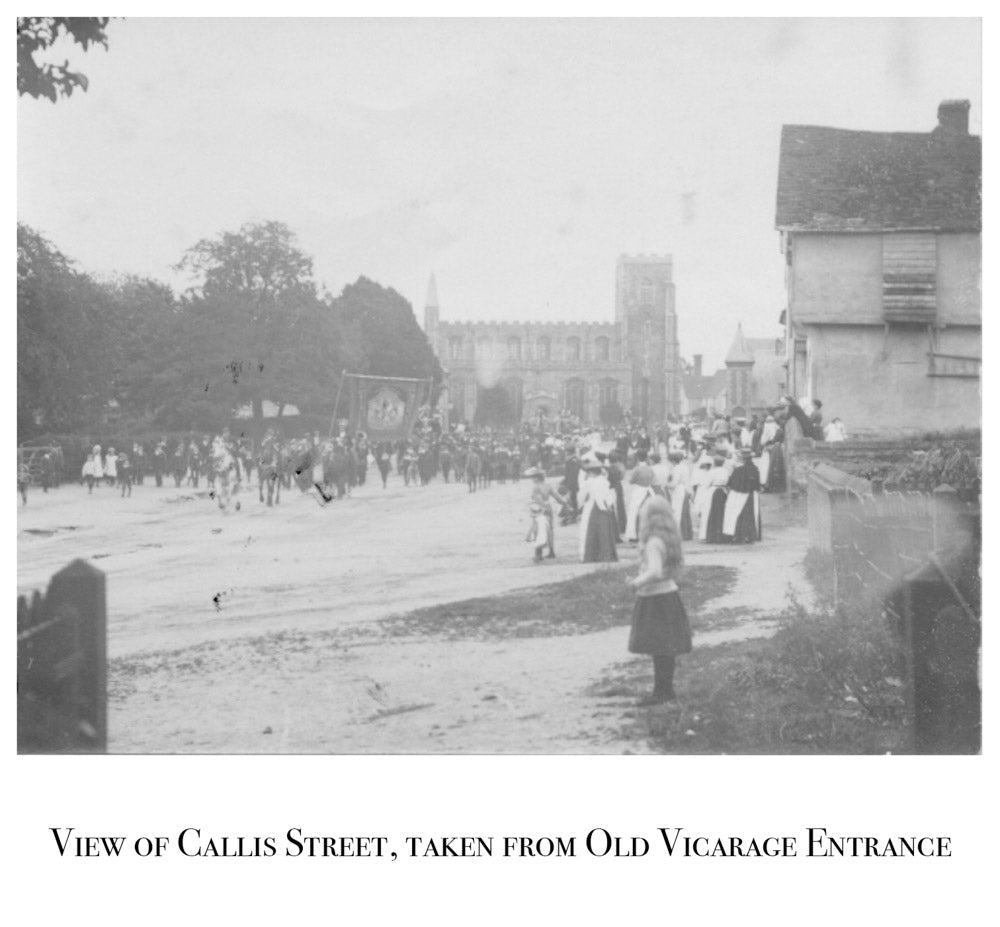

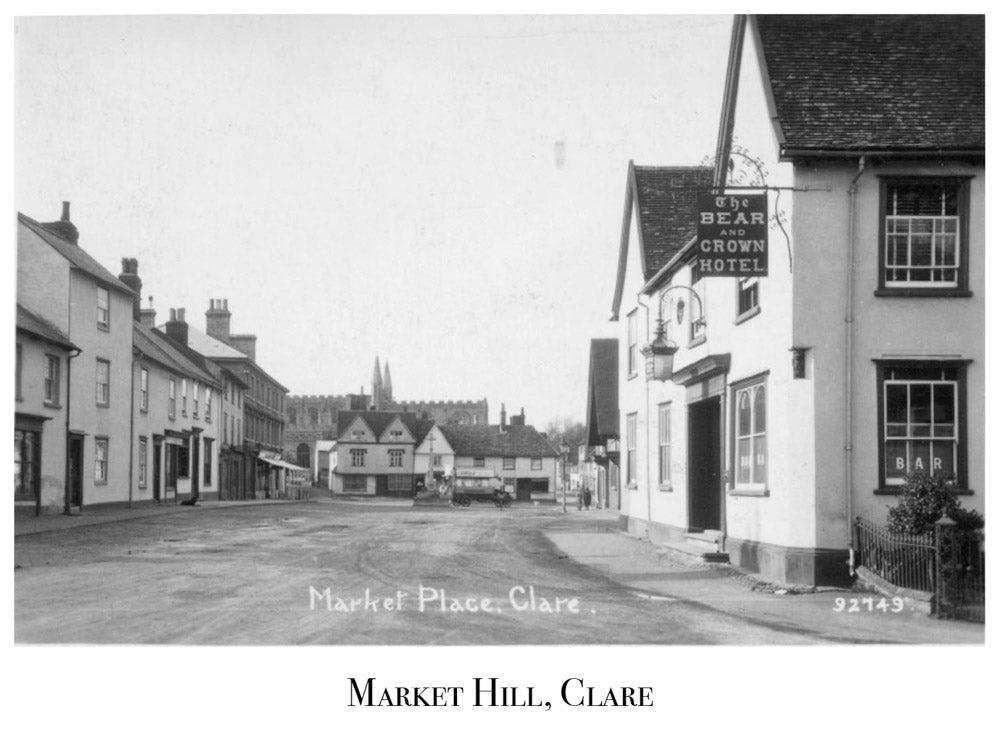

Below are some interesting images we found whilst doing research. Though most are unrelated to ironmongery in Clare, we thought we would include them anyway.

This article could not have been compiled without the help of Olive Smith, Barbara Peck, Mick Hickford, Robert Rush, Peggy Smith, Peter Trinder, William Dennis, Audrey Frost Gloria Orbell, Robin Stone and Don Harding, all of whom we are thankful for the images and information they have donated towards this project.

5 comments

Avinash Sharma on Sep 20, 2016

Been to Clare thrice. What a place it is. Beautiful, peaceful and what not. The local sights are awesome to hang out at. The weather is absolutely amazing. Also impressed by the food and hospitality of the local residents. Would love to be back here. Avinash Sharma on September 20, 2016

Peggy Smith on Sep 19, 2016

Well done in turning up some great photos that haven’t yet made it into Clare Ancient House Museum. Especially valuable are the ones that record their ironwork on gates around Clare, and the ones that show Peck & Bloomfield in their workshops. A record of work by the Suffolk Latch Company will also be valuable for future residents of Clare to see.

Mary Evason on Sep 18, 2016

Wonderfully written article. I had no idea how much of Peck & Bloomfield’s work was still in existence. I was also unaware of just how influential the Orbell family were to this community. I would love to read more!!! keep up the great work.

William Burns on Sep 17, 2016

Fantastic article . Well done

Sally Brown on Sep 16, 2016

I loved reading this, thank you. It’s amazing when you stop to look just how much of their work is still prominent in Clare today.